On Empathy, “emotional justice,” and Connection: A Collaboration Between Picture Books to Grow and Inside/Out

“Emotional justice requires that we find the feeling behind the theories. It calls on us to not just speak to why something is problematic, but to speak to the emotional texture of how it impact[s] us; how it hurts, or how it brings us joy or nourishment.” - (Crunk Feminist Collective)

We can live in such a cruel culture. There are things that seem impossible to explain to children. This list is long and just seems to get longer every day: climate change, white supremacy, settler colonialism. My children ask impossible questions: Why can’t we just give the land back if it’s not ours? Why do people want money more than trees? How to answer, I truly don’t know.

In This Accident of Being Lost, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson begins to get at the Kafkaesque paradox of taxes given settler colonialism:

“Good one, Kwe. Good one. You can go on and on and on about taxes. First you Canadians stole the land, then you make up this elaborate system of oppression to keep us too dead or too depressed to do much about it, then you create this elaborately irritating system for us all so that you have the cash to maintain the deadened depression, and, admit it, Revenue Canada irritates the fuck our of you guys too, it’s like our first point of agreement, and then, to add salt to our wounds, you make us figure out how much zhoon we gotta pay for the oppression…. while perpetuating the myth that I don’t even pay taxes.”

What can we do in the face of such Byzantine cruelty? As Simpson ultimately reminds us, we need to try to explain the inexplicable if we are ever to have change, to build in the face of destruction, to connect through walls, to generate empathy rooted in relationship and communication. So while our beautiful, challenging world often seems so impossible, drop by drop, an ocean is filled, and resistance and change, a vision of a different world, begins to take shape.

In a departure from previous posts, this edition was created in collaboration with Inside/Out, a group dedicated to supplying books and other forms of support to people who are affected by incarceration. It features both a picture book and an “adult”-oriented print book and draws parallels between their themes, making the argument that the messages and content of both formats are equally relevant and affecting, and that neither are impenetrable or age-specific.

We’ve worked to highlight what Crunk Feminist Collective calls themes of “emotional justice,” recognizing, reckoning and “working with that wounding” caused by our world’s white supremacy, violence, colonialism, and so much more, and reasserting and forging new connections and communities where they have been injured or sabotaged.

When We Were Alone

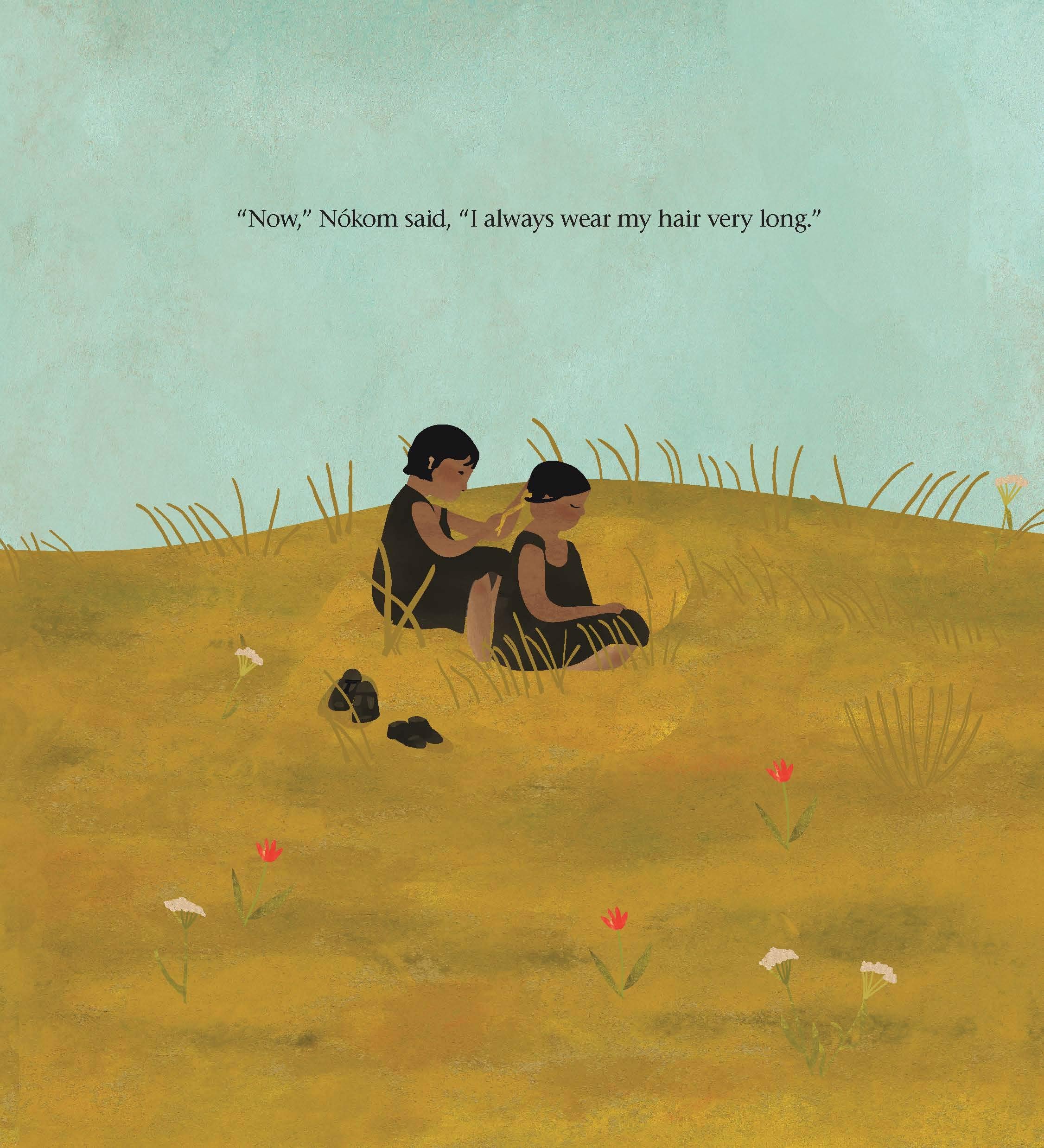

by David A. Robertson, illustration by Julie Flett

This beautiful and gentle picturebook is helpful in beginning to talk to children about anti-Indigenous racism and the history of settler colonialism and residential schools. It involves a little girl talking to her grandmother, and asking her grandmother a number of questions, including why does her grandmother have long and braided hair, why does she love sitting and talking with her family members so much, and why does she wear brightly coloured clothing. Her grandmother gently points to the connections between her behaviour and clothing now, and the history of residential schools that sought to strip her of her Indigenous identity.

The book’s tag phrase “when we were alone” is a direct arrow to the heart, as her grandmother remembers that in the residential school they cut off her hair, but when she and the other children “were alone” they braided grass into their to pretend it was long again. Or, to the question as to why she loves to spend so much time with her family, she remembers that, before the school, when she was a child, family was the most important thing. But when she was taken to the residential school, she and her brother were separated, but sometimes they could sneak off “when we were alone” to spend time together again, and they would take off their mittens and hold each other’s hands. Now she tells her granddaughter, “I am always with my family.”

When I was in graduate school, a painting hung on the wall of a friend of mine of two women friends or lovers holding hands, and on the top it said “They are even afraid of our songs of love.”

Like the best children’s books, When We Were Alone not only reminds us of the history of residential schools, but also the importance of connection, whether it is with our biological families or our chosen families or both at once. I think of the last line of this book often to remind myself of the importance of holding my family and friends close.

Abolitionist Intimacies

by EL Jones

El Jones’ Abolitionist Intimacies is a print nonfiction book that is both defiant and elegiac. Here, we move from the carcerality of residential schools to that of the prison system (a connection made plain by Jones in this Halifax Examiner article). Through a blend of personal stories, political writing and hip-hop-inflected poetry, Abolitionist Intimacies takes When We Were Alone’s pinpoint descriptiveness to a coast-to-coast canvas. It is a resolutely and radically humane examination of incarceration and the people it affects–in Canada and beyond–and a book-long commitment to relationship-building, to humanization, and to family-making in the face of cruelty and dispossession.

The core of the book is Jones’ descriptions of her relationships and work with and on behalf of people affected by incarceration. For those on either side of the prison walls, attempts to connect are heavily policed–phone calls are recorded, visits are subject to searches–and are weighted with the threat of punishment.

Descriptions of these interactions not only illuminate the realities and results of the carceral system–she ably ties these interactions to larger, systemic issues–but purposefully work against the all-consuming threat of criminalization, of a stigma that forces all associated with incarceration to “cross over” to “the ‘other’ side of society.” Jones’ writing is nuanced, personal, and she shows herself gifted at embracing and exploring the complexities of developing and maintaining relationships under fraught circumstances.

The book also works to denude the notion that change or “reform” stems from the academy, government or legal system, and shows time and time again how instruments of the “justice system” lead to disconnection or death; in short, a threat of assimilation or extinction. Instead, she writes, “we know the work of abolition lives in our communities every day, including in our refusal to abandon or dehumanize those living inside the walls.”

Akin to the grandmother of When We Were Alone deriving strength by reasserting a forbidden family, Abolitionist Intimacies argues and illustrates that “love, desire, care, longing, touch, and humanity assert themselves against prison walls. These expressions of human relations are dangerous to the prison regime.”

It is a fulsome relationality and intimacy that Jones depicts in resistance, one consisting of “trust, friendship, keeping my word, meeting needs, and moving beyond either neoliberal system-based interventions (social work, nursing staff, programmers) into everyday caring relationships.” The bonds Abolitionist Intimacies seeks to broker, then, are stronger than the bars of any prison.

There are so many bridges with which to traverse difference and cross over into empathy. Empathy is hard, harder on the days when even changing the clothes from the washing machine to the dryer seems impossible, let alone crossing an imaginary emotional bridge. And yet, we need to keep trying since, in the words of journalist Amanda Ripley in her book High Conflict, we can’t keep treating one another this way: “We are stuck with each other.” Art, poetry and picturebooks are tried and true ways of crossing the empathetic bridge that so often divides us.

When We Were Alone and Abolitionist Intimacies both vivify this emotional bridging, and share a poetic, personal, and radical core. Whereas our world seemingly imprisons, punishes, and segregates unblinkingly, these works offer alternative visions of relation and emotional connection that can resonate among all readers.

If you would like to learn more about Inside/Out, you can find them on Instagram & Facebook.

If you have any questions about their work, books to donate, etc. you can reach the lovely folks behind this project at: incarcerationbooks@gmail.com